Harmful speech includes hate speech, mis/disinformation, harassment and incitement.

In common language, “hate speech” refers to offensive discourse targeting a group or an individual based on inherent characteristics (such as race, religion or gender) and that may threaten social peace.

To provide a unified framework for the United Nations to address the issue globally, the UN Strategy and Plan of Action on Hate Speech defines hate speech as…“any kind of communication in speech, writing or behaviour, that attacks or uses pejorative or discriminatory language with reference to a person or a group on the basis of who they are, in other words, based on their religion, ethnicity, nationality, race, colour, descent, gender or other identity factor.”

However, to date there is no universal definition of hate speech under international human rights law. The concept is still under discussion, especially in relation to freedom of opinion and expression, non-discrimination and equality.

Watch the video in Sinhala and Tamil.

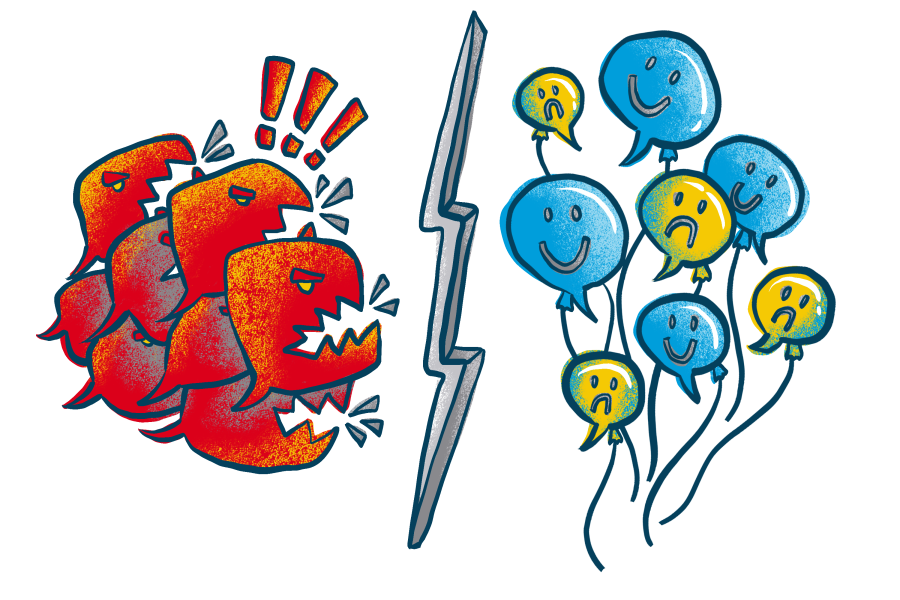

What is the difference between mis- and disinformation?

The difference between mis- and disinformation lies with intent. Disinformation is information that is not only inaccurate, but is also intended to deceive and is spread in order to inflict harm.

Misinformation refers to the unintentional spread of inaccurate information shared in good faith by those unaware that they are passing on falsehoods. Misinformation can be rooted in disinformation as deliberate lies and misleading narratives are weaponized over time, fed into the public discourse and passed on unwittingly.

In practice, the distinction between mis- and disinformation can be difficult to determine. Mis- and disinformation and hate speech are related but distinct phenomena, with certain areas of overlap and difference in how they can be identified, mitigated and addressed. All three pollute the information ecosystem and threaten human progress. It can affect a broad range of human rights, undermining responses to public policies or amplifying tensions in times of emergency or armed conflict.

Watch the video in Sinhala and Tamil.

Hate speech versus freedom of speech

“Addressing hate speech does not mean limiting or prohibiting freedom of speech. It means keeping hate speech from escalating into something more dangerous, particularly incitement to discrimination, hostility and violence, which is prohibited under international law.” - United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres

The need to preserve freedom of expression from censorship by States or private corporations’ is often invoked to counter efforts to regulate hateful expression, in particular online.

Freedom of opinion and expression are, indeed, cornerstones of human rights and pillars of free and democratic societies. These freedoms support other fundamental rights, such as to peaceful assembly, to participate in public affairs, and to freedom of religion. It is undeniable that digital media, including social media, have bolstered the right to seek, receive and impart information and ideas. Therefore, legislative efforts to regulate free expression unsurprisingly raise concerns that attempts to curb hate speech may silence dissent and opposition.

To counter hate speech, the United Nations supports more positive speech and upholds respect for freedom of expression as the norm. Therefore, any restrictions must be an exception and seek to prevent harm and ensure equality or the public participation of all. Alongside the relevant international human rights law provisions, the UN Rabat Plan of Action provides key guidance to States on the difference between freedom of expression and “incitement” (to discrimination, hostility and violence), which is prohibited under criminal law. Determining when the potential of harm is high enough to justify prohibiting speech is still the subject of much debate. But States can also use alternative tools – such as education and promoting counter-messages – to address the whole spectrum of hateful expression, both on and offline.